Researcher of the Future — a Confidence in Research report

Discover mission-critical insights into how researchers are turning disruption into discovery.

Unfortunately we don't fully support your browser. If you have the option to, please upgrade to a newer version or use Mozilla Firefox, Microsoft Edge, Google Chrome, or Safari 14 or newer. If you are unable to, and need support, please send us your feedback.

We'd appreciate your feedback.Tell us what you think!

News, information and features for the research, health and technology communities.

Discover mission-critical insights into how researchers are turning disruption into discovery.

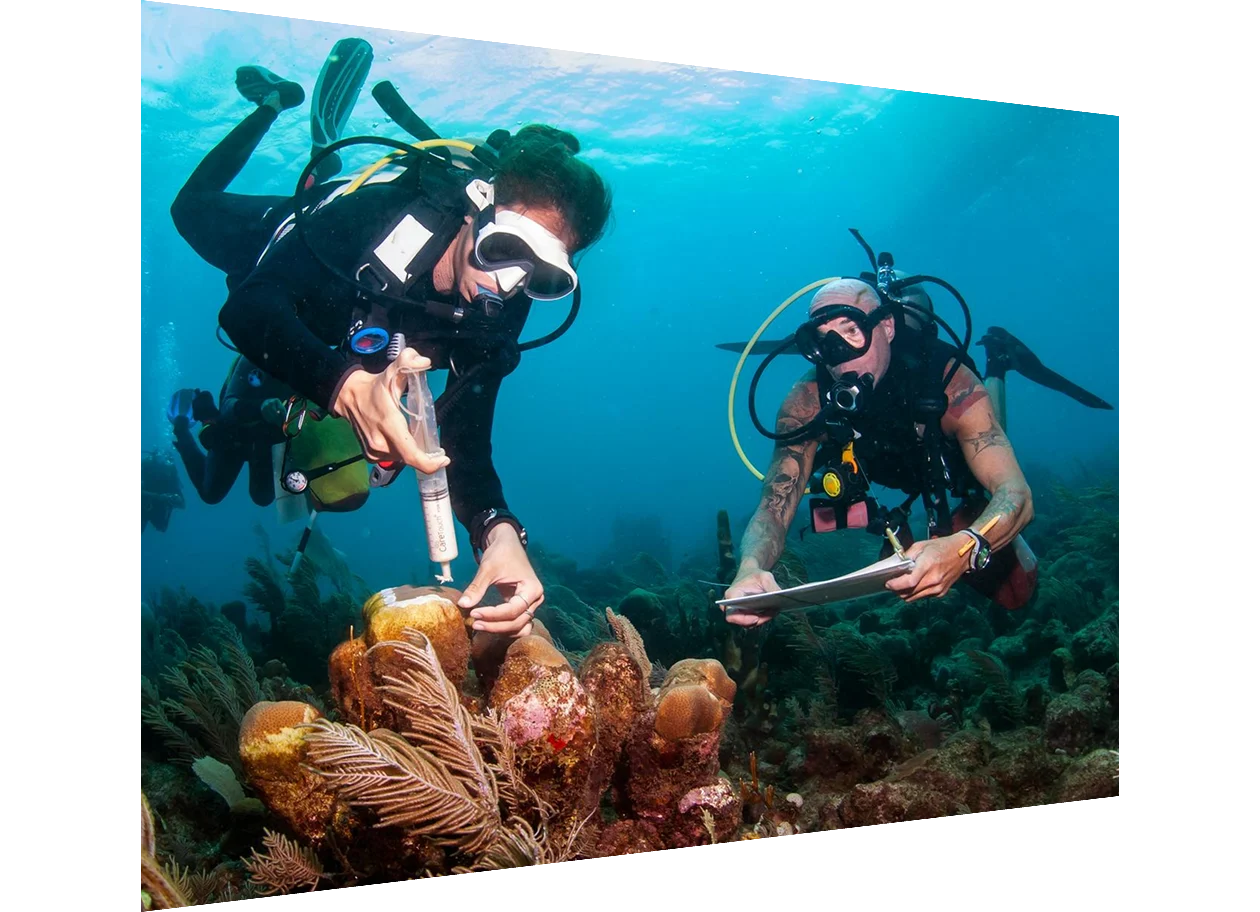

Cuttlefish and cephalopods are unlocking secrets of memory, inspiring cutting-edge technology, and reshaping biomedicine. From false memories to squid-inspired optical breakthroughs, these marine marvels are driving innovation across disciplines. Dive in to discover how nature’s ingenuity can help solve today's biggest challenges.