Together we created the most advanced 3D female anatomy model

April 1, 2022

By Terri Mueller

The team behind 3D4Medical’s female anatomy model talks about how they developed it — and why it has far-reaching implications for medicine

Editor's note: For too long, anatomical models have focused on the male body. Now, Elsevier Health has brought the first complete 3D representation of the female anatomy to life. The female model provides far more insight into the workings of human anatomy and creates greater parity in our understanding of female and male bodies.

Here, we introduce the team that conceived and delivered this breakthrough and show how it can help more than 1 million health educators and medical professionals worldwide.

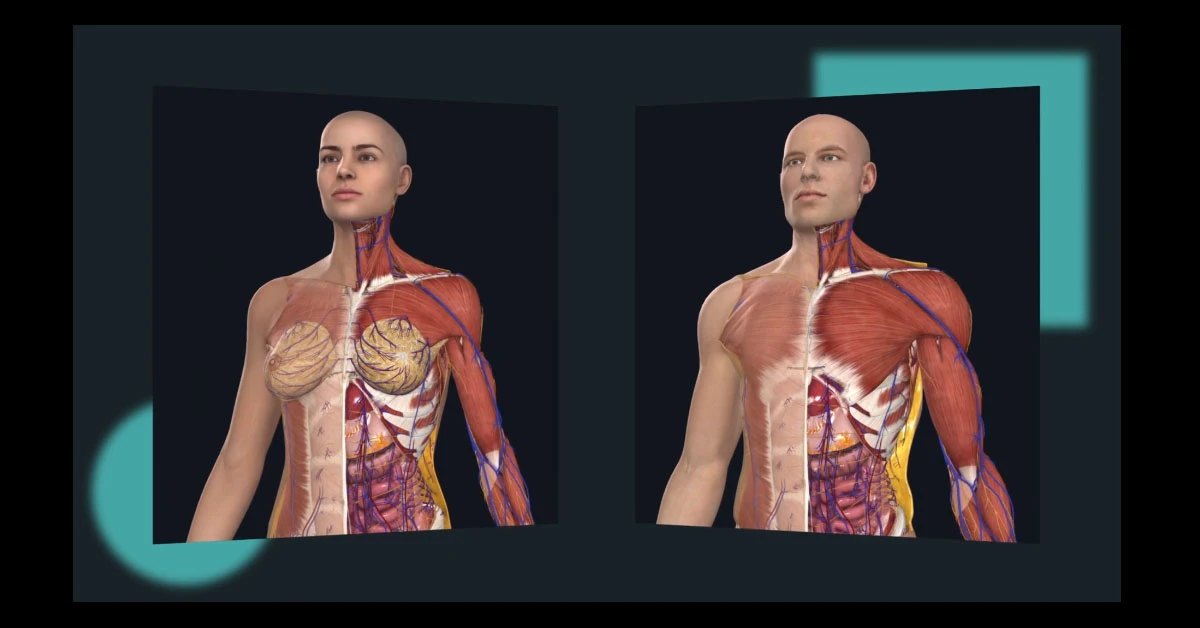

With Complete Anatomy's new full female model, created by Elsevier's 3D4Medical, users can switch between detailed female and male images with one click.

Based in Dublin, Ireland, Elsevier’s 3D4Medical team has spent years creating the world’s most advanced 3D female anatomy model, which they recently released through Elsevier’s Complete Anatomy app.

For centuries, the study of anatomy was largely limited to the male, often European form. Female and non-European bodies were considered only in terms of how they were different from the male rather than being represented in their own right.

This systemic, often unconscious bias continues today, with far-reaching implications for the medical diagnosis and treatment of women, ethnic minorities, transgender and non-binary communities. Did you know, for example, that in the UK, Black women are four times more likely to die in pregnancy or childbirth?

Relying on the male anatomy to form the basis of our medical understanding of all people is fundamentally flawed, and yet even today, anatomy textbooks focus primarily on the male body. The female anatomy is often only considered important in terms of the reproductive organs, with diagrams showing women in the lithotomy, or childbirth, position.

Elsevier’s complete 3D female anatomy model stands shoulder-to-shoulder with the male figure for the very first time, taking a giant step towards tackling the unconscious bias that exists across the medical profession.

This project has been the focus of a dedicated team of experts who have battled technical and anatomical challenges to bring this idea to fruition.

Irene Walsh is Director of Product, Design & Content at 3D4Medical from Elsevier. As the leader of the product team, Irene was the one who pitched for this project to be added to the Elsevier roadmap, and then to oversee its delivery. She says:

Creating the 3D female model was so important to us because of the societal impact we knew it would have. It was about stepping up and being able to contribute something really positive to the world of learning anatomy. It was about being part of a company like Elsevier, whose overall goal is to drive better patient outcomes, reinforcing the feeling you’re contributing to something bigger.

Irene Walsh

The inclusivity journey

Alan Delmar is a Product Manager at 3D4Medical from Elsevier. His work tends to be quite data driven, but the female anatomy project gave him the opportunity to work on something unique as part of an expert team of designers, user experience (UX) managers, artists and medical experts. He explains:

My role as Product Manager was the end-to-end management of the whole process, from conceptual conversations about how best to create the model, right through to resolving design problems and developing our market strategy.

Alan Delmar

What I really love about my work is that it is intensely collaborative, involving problem solving and working closely together as a team. I’m used to making quite clear-cut decisions based on data, but this was a much more challenging project because we really wanted to tackle the old-fashioned thinking processes that have caused such systemic bias across the medical community.

This determination led the team to in-depth conversations about ancestry and skin tone — and whether it was appropriate to create the female model as a light-skinned European female. Instead, they chose a skin tone and phenotype for the female that represented a much wider demographic while still staying accurate to the underlying anatomy.

This female model is only the first step Elsevier is taking on a very long journey towards total inclusivity, with plans already in place for the creation of diverse ancestry models with a much broader range of skin tones and phenotypes, as well as models of transgender and intersex people. Irene adds:

We’ve been asked why we’re bothering about skin layers because it’s not so relevant in anatomy, but if you’re showing skin at all then you’re automatically making a statement, and we felt it was our duty to be more representative.

Getting the anatomy right

Ashton Luxgrant is the head medical writer at 3D4Medical from Elsevier. She joined Elsevier 18 months ago, and the female anatomy project was the very first she worked on. With a master’s degree in anatomy, she was perfectly placed to understand the pre-existing bias in the medical community, something that helped fuel her passion for the project. She says:

It was a daunting project to take on, but I loved the idea of making teaching anatomy more equal; highlighting the importance of having a whole female model instead of it just being broken up into different pieces.

Ashton Luxgrant

Ashton carried out much of the main research into the female anatomy, exploring the key differences of the female skeleton and making sure they were correctly recognized and represented.

“You can’t just take the male model and shrink it,” she says. “We realized there was a lack of research when it comes to certain female organs, so we spoke at length with subject matter experts to find the most up-to-date and accurate anatomy.

“Knowing that the work I do is going to have such a positive impact on medical students and people all around the different sciences learning anatomy has been amazing. I really feel that what I’m working on at Elsevier matters.”

Overcoming technical challenges

Creating the most advanced female anatomical model on the market, with more than 17,000 selectable structures, brings with it some serious technical challenges, not least around the size of the app and how to make it all accessible on a smartphone or tablet. Overcoming these technical obstacles, while preserving the vision and integrity of the female model, was the first major challenge of the 3D modeling team.

Ultimately, the decision was made to shift the architecture from a bundled model to an on-demand one, with content only downloaded when needed.

As Head of 3D, Gusztav Velicsek is a 3D modeler and texture artist who oversaw the artistic modeling team and the design of the female model.

“I had the privilege of having a birds-eye view of the product,” he says. “We started with the skeletal system, measuring every last bone in the body, making sure they were accurate and relevant to as many women around the world as possible.

Gusztav Velicsek

“Once we had checked our results with subject matter experts, we started work on the skin tones and the model’s finished look. We wanted to create a skin that would not only be accurate, but would aesthetically represent feminine characteristics so that it didn’t feel like a modified male model.”

For Gusztav, it was important to treat the female model with the utmost respect:

We had so many conversations with our female colleagues over the course of the project to discuss how under-represented female anatomy is and how this imbalance could be redressed. We can’t rewrite history, but we can help to change the future.

Mark Whitty was the 3D generalist that worked on the skin layer for the female 3D model. He was responsible for finding her character and making her look believable and approachable. He says:

As males working on a project like this, it would have been easy to make assumptions, but while we looked after the technical and artistic aspects of visualizing the female model, we always talked to our female colleagues so they had the leading voice.

Mark Whitty

As the 3D artist tasked with creating the anatomical detail, Matthew Innes says he’s found the entire project to be very fulfilling:

Working on the female reproductive anatomy was certainly challenging as there is a lot of complex, highly detailed anatomy which is often quite abstract and poorly represented. It was a difficult but also fun challenge which required multiple people across different disciplines to create something of quality, clarity and accuracy.

Creating the user experience

The success of any app has a lot to do with the UX. Making sure it is easy for users to find the information they’re looking for was the responsibility of Lead UX Designer Jennifer Massey .

She worked closely with users during the early testing phase, establishing the flows that would make the app intuitive, and establishing the interactions users would have with the new female model. She explains:

Jennifer Massey

What became clear from talking to users was that representation was the major problem. Half the population didn’t feel represented, and there are a lot of other problems around learning outcomes and treating people in clinical situations when you’re only learning about the male form.

She worked with Alan to gather all these issues together and with the medical and design teams to find the best solutions:

There were lots of decisions we had to make while creating the female model that you wouldn’t have with a man, for example, is she perceived to be too pretty? Is she being over-sexualized? We had to be extra careful and really think through every decision, and never just assume. We also wouldn’t have learned what we did without speaking to experts in the subject matter.

I loved working with everyone on the team. At Elsevier you get to work on really complex projects that are about doing the right thing. We’re disrupting how anatomy is learned and the fact that we get to think about these things – very few people get the opportunity for that level of job satisfaction.

Contributor

Terri Mueller

Vice President of Communications, Health and Industry Markets

Elsevier

+1 908 323-9180

E-mail Terri Mueller