Temperature-sensitive bionic hand improves dexterity and feelings of human connection

15 février 2024

Par Liana Wait, PhD

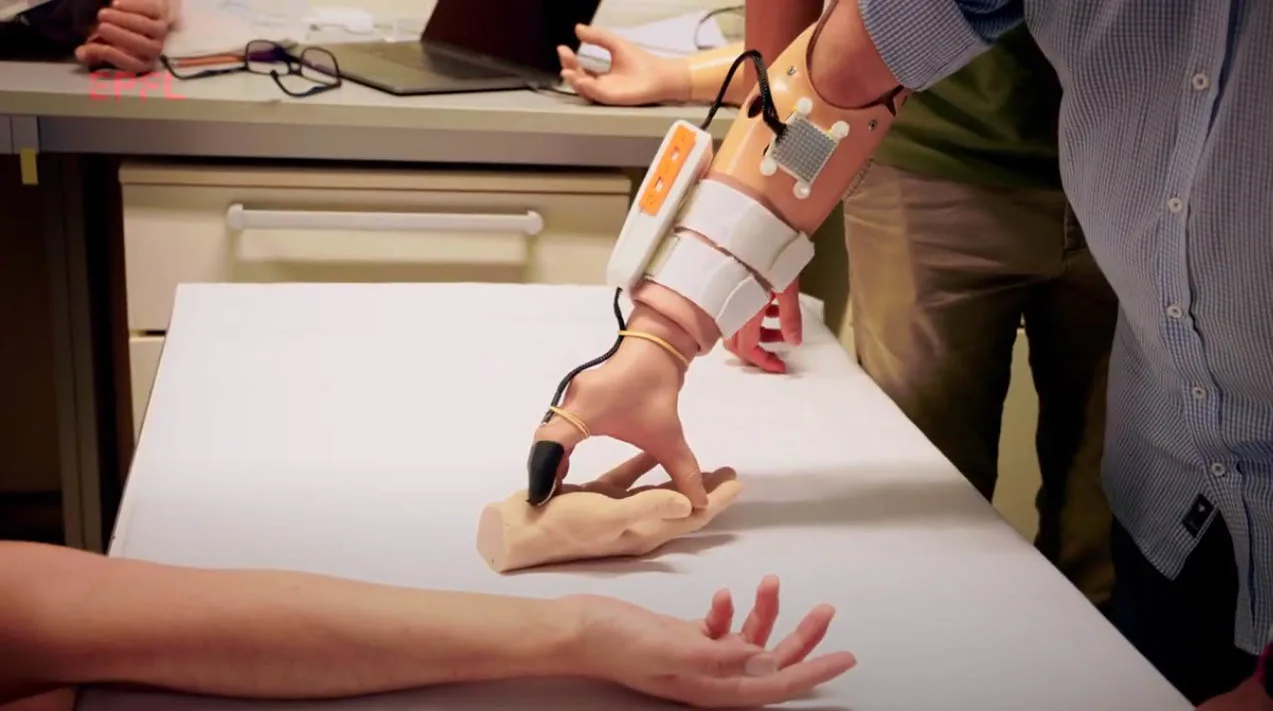

Using the thermally sensitive prosthetic hand, a 57-year-old transradial amputee was able to manually sort objects of different temperatures and sense bodily contact with humans. (Credit: EPFL Caillet)

“For the first time, we’re really close to restoring the full palette of sensations to amputees.” — Neuroengineering researcher Prof Silvestro Micera reporting on new study

Sensory feedback is important for amputees to be able to explore and interact with their environment. Now, researchers have developed a device that allows amputees to sense and respond to temperature by delivering thermal information from the prosthesis’s fingertip to the amputee’s residual limb. The MiniTouch device, presented February 9 in the Cell Press journal Med, uses off-the-shelf electronics, can be integrated into commercially available prosthetic limbs, and does not require surgery. Using the thermally sensitive prosthetic hand, a 57-year-old transradial amputee was able to discriminate between and manually sort objects of different temperatures and sense bodily contact with other humans.

“This is a very simple idea that can be easily integrated into commercial prostheses,” says senior author Prof Silvestro Micera of École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL) and Scuola Superiore Sant’Anna. “Temperature is one of the last frontiers to restoring sensation to robotic hands. For the first time, we’re really close to restoring the full palette of sensations to amputees.”

“This is a very simple idea that can be easily integrated into commercial prostheses. Temperature is one of the last frontiers to restoring sensation to robotic hands. For the first time, we’re really close to restoring the full palette of sensations to amputees.”

SM

Silvestro Micera, PhD

Bertarelli Foundation Chair in Neuroengineering at École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne | Professor of Neural Engineering at Scuola Superiore Sant’Anna

Exploiting phantom thermal sensations to create “the feeling that this hand is mine”

The team previously showed that their thermosensitive technology could restore passive thermosensation in 17/27 amputees. In the new study, they show that the MiniTouch can be easily integrated into commercial prosthetic limbs and that it enables active thermosensation during tasks that require feedback sensory motor integration.

As they explain in their study summary:

Recently, we reported the presence of phantom thermal sensations in amputees: thermal stimulation of specific spots on the residual arm elicited thermal sensations in their missing hands. Here, we exploit phantom thermal sensations via a standalone system integrated into a robotic prosthetic hand to provide real-time and natural temperature feedback.

Beyond the functional importance of being able to sense hot and cold, thermal information could also improve amputees’ sense of embodiment and their ability to experience affective touch. “Adding temperature information makes the touch more human-like,” says senior author Dr Solaiman Shokur, Senior Scientist in the Translational Neuroengineering Laboratory of EPFL. “We think having the ability to sense temperature will improve amputees’ embodiment — the feeling that ‘this hand is mine.’”

In their graphical abstract, the researchers show how their device can enable an amputee to differentiate between temperatures, materials, and artificial and human contact. (Source: Muheim and Iberite et al: Med, Feb 2024)

Methods

To do this, they integrated the MiniTouch into the personal prosthesis of a 57-year-old male who had undergone a transradial amputation 37 years earlier by linking the device to a point on the participant’s residual limb that elicited thermal sensations in his phantom index finger. Then they tested his ability to distinguish between objects of different temperatures and objects made of different materials.

Researchers test their bionic hand

Watch now

|

Researchers test their bionic hand

Results

Using the MiniTouch, the participant was able to discriminate between three visually indistinguishable bottles containing either cold (12°C), cool (24°C) or hot (40°C) water with 100% accuracy, whereas without the device, his accuracy was only 33%. The MiniTouch device also improved his ability to sort metal cubes of different temperatures quickly and accurately.

“When you reach a certain level of dexterity with robotic hands, you really need to have sensory feedback to be able to use the robotic hand to its full potential,” Dr Shokur explains.

Finally, the MiniTouch device improved the participant’s ability to differentiate between human and prosthetic arms while blindfolded — from 60% accuracy without the device to 80% with the device. However, his ability to sense human touch via his prosthesis was still limited compared to his uninjured arm, and the researchers speculate that this was due to limitations in other non-thermal sensory inputs such as skin softness and texture. Other technologies are available to enable these other sensory inputs, and the next step is to begin integrating those technologies into a single prosthetic limb.

Next steps

“Our goal now is to develop a multimodal system that integrates touch, proprioception, and temperature sensations,” says Dr Shokur. “With that type of system, people will be able to tell you ‘this is soft and hot,’ or ‘this is hard and cold.’”

The researchers say their technology is ready for use from a technical point of view, but more safety tests are needed before it reaches the clinic, and they have plans to further improve the device so that it can be more easily fitted. Future models could also build upon the Minitouch to integrate thermal information from multiple points on an amputee’s phantom limb — for example, allowing people to differentiate thermal and tactile sensations on their finger and thumb might help them grasp a hot beverage, while enabling sensation in the back of the hand might improve the feeling of human connection by allowing amputees to sense when another person touches their hand.

Read the study

Muheim and Iberite et al: “A sensory-motor hand prosthesis with integrated thermal feedback,” Med (Feb 9, 2024)

Med, Cell Press's flagship medical journal, publishes transformative, evidence-based science across the clinical and translational research continuum — from large-scale clinical trials to translational studies with demonstrable functional impact, offering novel insights in disease understanding.

Contributeur

LWP