The 5 most powerful self-beliefs that ignite human behavior

September 16, 2015 | 9 min read

By Bobby Hoffman, PhD

Self-beliefs influence our goals, strategies and accomplishments. Do you know which self-beliefs dominant your daily behavior?

Educational psychologist Dr. Bobby Hoffman(opens in new tab/window) is an Associate Professor in the School of Teaching, Learning & Leadership at the University of Central Florida and author of Motivation for Learning and Performance(opens in new tab/window), published by Elsevier’s Academic Press in July. This is the second in a series of articles, he is writing for Elsevier Connect. The first was: “5 pitfalls to understanding people’s motives.”

Understanding human behavior is based in part upon a conscious awareness of self-beliefs. These beliefs drive our underlying motives, which influence our purpose, characteristics, interests, and idiosyncratic attributes that determine who we are.

Most people have little insight into what ignites their day-to-day behavior, according to scientific evidence. Often described as motives, the instrumental forces that drive and direct our behavior are based on a series of tacit beliefs that we have about ourselves. In aggregate, these self-beliefs determine the direction and intensity of our motivated action. The beliefs determine what we do, how we do it, and how we see our accomplishments in relation to the rest of the world.

Self-beliefs are so powerful that the evaluations will strongly influence the careers we seek, the relationships we pursue, and ultimately what we do or do not accomplish in life.

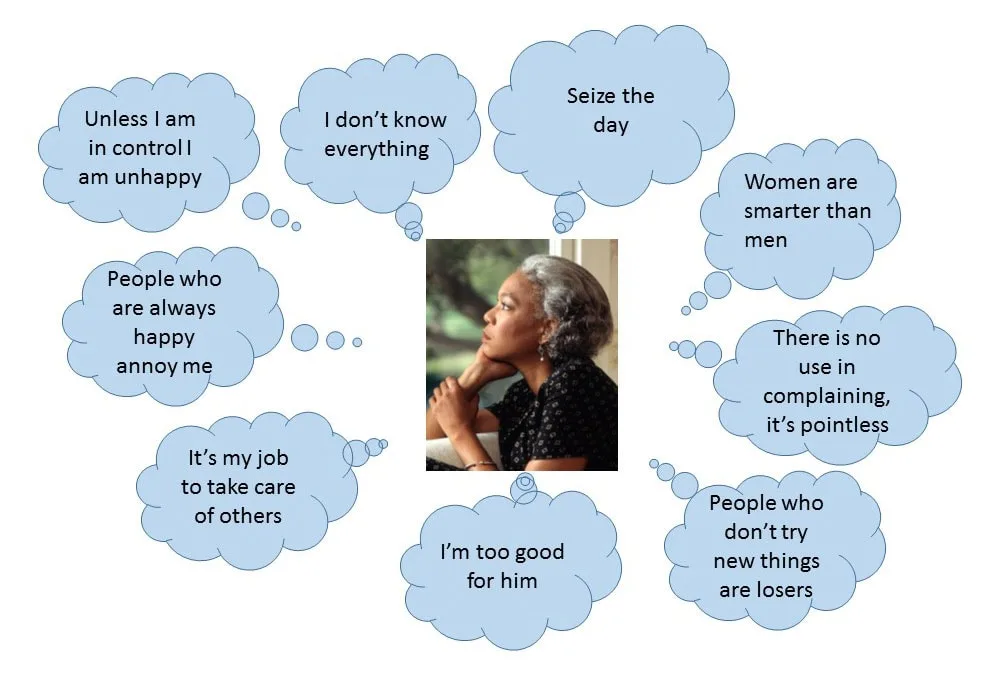

Ironically, if I asked you to name which self-beliefs influence you most you probably wouldn’t know where to begin. Beliefs are implicit, which means many of the personal theories we have about ourselves operate automatically and unconsciously.

Self-beliefs are not religious, political or secular views and don’t include things such things as how you like your eggs cooked or whether you think reading is a more effective strategy for knowledge gain than watching videos. Instead, self-beliefs are the guiding principles and assessments we make about our personal capabilities and what outcomes we expect as a result of our efforts. By bringing these beliefs to the forefront of consciousness, people can take steps to harness the power and influence of their beliefs. But what are these mysterious beliefs that determine the totality of our being?

1. Control

The most dominant self-belief is our assessment of the degree of control we have over our own destiny. Control beliefs dictate whether pursue goals and task for reasons external to the psychic self or to satisfy the inner psychological strivings of the core self. People with an external focus feel that their destiny is not within their direct control. Diminished control beliefs result in ascribing life events and accomplishments to fate, luck or circumstances the individual cannot or will not influence, such as what happens when a person believes they are stuck in a tedious job because of poor market conditions. Frequently individuals with an external perspective will not seek challenges and will avoid setting stretch goals, settling instead for the status quo. Conversely, people with strong control beliefs feel in command of their perceptual world. They believe they can orchestrate their career, social relationships and lifestyle. The internal focus acts as a catalyst for personal growth and development because the individual takes responsibility and is accountable for their own success or failures.

2. Competency

Competency beliefs are also highly influential for motivated behavior. Competency beliefs include assessments of our overall ability to achieve desired outcomes but can also reflect micro-level assessments of the perceived skills and abilities needed to complete a task, such as writing an article or installing computer software.

The sources of competency appraisals are varied; some are based on past performance, while others focus on current challenges or on the anticipation of gaining desirable outcomes. Individuals will tend to appraise their degree of competence not entirely upon actual ability and knowledge but upon presumed competency beliefs, including the perception of the individual by others.

Competency assessments can influence perceptions of overall self-worth and can be the deciding factor in determining whether a person will engage in a task or elect to defer, withdraw or completely avoid a challenge. Task avoidance is motivated by fear of failure based on a perceived likelihood of undesirable evaluations from others, or because of the dismal prospect of generating negative emotions such as doubt, guilt, or humiliation that often accompany task failure.

The author’s new book

In Motivation for Learning and Performance(opens in new tab/window), published by Elsevier’s Academic Press, Dr. Bobby Hoffman explores why we do the things we do, including strategies to change our own behavior and exert greater influence on those around us. He outlines 50 key motivation principles based on the latest scientific evidence from the disciplines of psychology, education, business, athletics and neurology. For examples, he interviewed highly influential people, including Bernie Madoff, country music star Jessi Colter, Florida Senator Darren Soto, NFL veteran Nick Lowery, and actress Cheryl Hines.

Dr. Hoffman draws on his expertise in educational psychology and a 20-year career in human resources management and performance consulting.

Motivation for Learning and Performance (elsevier.com)

3. Value

A third influential self-belief is the degree of value we associate with different task outcomes, which fluctuates according to individual and culture standards as well as the extent of cognitive, social and moral development. When ascribing low value to a potential goal or task, individuals are reluctant to invest effort. For example, who would devote extraordinary cognitive and financial resources to completing law school or invest physical energy toward running in a 10-mile race when the payoff is seen as marginal, uninteresting or of questionable value?

Value assessments include attainment value that represents the degree of relative importance the individual places on the contemplated task: intrinsic value, measured by how much an individual subjectively enjoys doing and completing the task, and utility value, which represents the perceived usefulness afforded to doing or mastering the task from an applied perspective.

Self-beliefs that ascribe little value to ethical and honest behavior may be one of the key reasons accounting for the frequency of what is described as moral disengagement, a practice whereby individuals and corporations are willing to engage in questionable business practices, lack of environmental concern, or deliberate law-breaking under the auspices of weak moral convictions.

4. Goal orientation

A fourth and highly influential self-belief relates to the reasons we pursue goals. Goal orientation represents the alleged purpose for engaging in learning or the reasons a particular performance target is chosen. Typically situated as an explanation of academic behavior, individuals may elect to pursue academic knowledge and personal development for either normative and appearance reasons or for the inherent satisfaction of mastering a skill or ability.

When goal pursuit is based upon an appearance belief, the individual is focused on looking good in the eyes of peers or avoiding the public humiliation that may accompany goal failure. This approach employs a social comparison motive because the individual is less concerned about results but more focused on the assessment of capability from others. Conversely, mastery-oriented individuals typically show greater interest in the accumulation of knowledge, unlike the cosmetic intentions of relative expertise endemic to the normative performer. The impact of orientation is highly instrumental in the strategies that individuals will use to reach their goals. Mastery performers are more inclined to seek help when needed, are better at monitoring their task progress, and are more willing to try new or alternative strategies to reach their desired outcomes than their egotistical peers.

5. Epistemology

Fifth, people have beliefs about the nature of knowledge acquisition and intelligence in general. While many different types of views may be espoused concerning “epistemology,” people fall into one of three categories when it comes to how knowledge is acquired and advanced:

Individuals may believe that knowledge is fixed, meaning there is one way, and only one way, to approach a problem or opportunity. People embracing this absolutist philosophy will adhere to dogmas, believing, for example, that the best jobs are only landed as a result of strong social connections and not through skill development.

Other individuals may assume a more flexible approach to thinking and believe that different opinions may be justified; they are willing to consider alternative perspectives (although usually deferring to their desired position).

Others will assess all views as equally warranted but believe that one position is clearly justified based on statutory, ethical or humanistic considerations, such as when people are motivated to devote time and resources to charitable causes because of it’s the “right” thing to do.

Closely related to epistemology beliefs are conceptions concerning general intelligence. Polarized views of intelligence suggest that individuals believe that intelligence is either subject to modification based upon the acquisition of new knowledge, representing an incremental view, or that intelligence, like flat feet or bushy eyebrows, is a reality that must be accepted, thus adopting an entity intelligence view. Assessment of the malleability of epistemological and intelligence views can prove quite useful because each view provides revealing clues as to the behavior individuals will exhibit regarding persuasion, negotiation and sales efforts during many facets of their lives. While the list of beliefs here is not inclusive, it is based on the confluence of evidence from educational, social and developmental psychology. Self-beliefs abound and clearly can be traced to many of the behaviors people exhibit in organizations, relationships and during the very basic transactions of human existence. While the science of behavioral prediction is indeed a slippery slope, traction can be gained by moving beyond the symptomatic evaluation of demonstrated behavior to a focus on which self-beliefs are most instrumental for motivated action.

The next article in this series will focus on how self-beliefs develop, with a particular focus on self-beliefs that affect learning and performance.

Contributor

BHP